Welcome to Everest 2024. The season begins soon, and I’ve already posted several Everest 2024 big-picture updates for this season:

- Everest 2024: Welcome to Everest 2024 Coverage – an introduction to the Everest 2024 Spring season.

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2024 Edition – My annual review of what it costs to climb Everest, solo, unsupported and guided.

- Everest by the Numbers: 2024 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2024 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard and non-standard.

This post takes a look at the climbing routes over the years – standard and non-standard.

2024 will be my 22nd season of all things Everest: 16 times providing coverage, another four seasons of actually climbing on Everest, and two years attempting Lhotse.

I summited Everest on May 21, 2011, and have climbed it three other times (all from Nepal) – 2002, 2003, and 2008, each time reaching just below the Balcony around 27,500′ (8400 meters) before health, weather or my judgment caused me to turn back. I attempted Lhotse in 2015 and 2016. When not climbing, I cover the Everest season from my home in Colorado as I did in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023 and now the 2024 season.

For 98% of all Everest climbers, the choice of routes comes down between the Northeast (Tibet) and Southeast (Nepal) Ridges. For almost everyone, all other routes are too dangerous, too difficult, and not commercially guided. This post will examine the various routes and explore the most popular commercial ones.

It may be an exaggeration to say that all the routes that can be climbed on Everest have been climbed because a new generation of climbers always blazes new trails. However, climbing Everest appears well understood across all aspects of the hill. There are about twenty named routes; almost all have been tried at least once, and most teams reached the summit.

Two still stand out as unclimbed today- the direct route up the East Face and the Fantasy Ridge, aka the East Ridge. Both are extremely dangerous and avalanche-prone. In years with little snow, one route was deemed unclimbable, as shown in 2006 by Dave Watson and the team on the Fantasy Ridge.

In 2009, a Korean team on the Southwest Face was the last team to complete a new route. In 2019, Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a valiant attempt to send a 6,551-foot direct line in a couloir, a narrow rock gully, on the Northeast face of Everest. The route began just above Advanced Base Camp at 21,325 feet on the Tibet side of Everest, leading into a gully that joins a high ridge and continues to a steep face and onto the summit. Eventually, they turned back at around 7,600 meters due to “conditions we encountered coupled with our chosen tactics compounded by exertion” after spending 40 hours on the wall with one open bivvy.

Preparing for Everest is more than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountain experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

2023 Review and 2024 Update

The 2023 Everest spring season ended with some records to take pride in and others to be avoided. If there were one word to summarize the season, it would be chaotic or perhaps deadly. This spring was the deadliest season in Everest’s history. It was also brutally cold.

Nepal issued a record 478 climbing permits to foreigners. Add in one and a half Sherpa supporting each foreigner; over 1,200 people pursued the summit last spring. Fears were rampant of a 2019 repeat with long lines and deaths. The lines never developed, thanks in part to colder weather that sent a higher number of climbers home in mid-season, many with a persistent virus. However, the deaths did develop, but not because of the record permits or climate change.

There were around 667 summits on the Nepal side and 16 from Tibet, which was still closed to foreigners. More Sherpas, 378, summited than clients, 277, according to the Himalayan Database. Only 55% of the members who went above Base Camp, 483, summited, 277. There was an all-time Everest high of 18 deaths – 6 Sherpas and 12 clients. In my estimation, 11 deaths were preventable.

What stole the headlines were the daily reports of rescues, frostbite, missing climbers, and deaths. The root cause of the chaos remains elusive and, in some cases, covered up. Some blame the record permit numbers, inexperienced clients, and low-cost operators. However, Nepal government officials cited climate change. Blaming climate change is a red herring to abdicate responsibility by operators and authorities. Again, in my estimation, 11 of the 18 deaths were preventable.

Continue reading about Everest 2023

I suspect 2024 will be another busy year. First, there is the insatiable lure of Everest, and, as is the standard since 2013, droves of inexperienced climbers drawn by “no-experienced required” low-cost operators. However, 2024 will be different, with the north side open to foreigners and the last year before Nepal raises permit pricing by 36%.

I expect 800 total summits from both sides this spring. Look for at least 150 Tibet-side total (members plus hired) summits and well over 650 on the Nepal side. With these numbers, they will still lag behind the pre-pandemic record set in 2019 of 877 total summits, comprising 661 from Nepal and 216 from Tibet. Last year, 2023, saw 655 total summits from Nepal and thirteen on Tibet. Let’s break all of this down and what our climbers can expect.

I expect 2024 to be a record year on Everest, with price increases across the board.

Follow the 2024 Everest Coverage!

2024 will be my 22nd season of all things Everest: 16 times providing coverage, another four seasons of actually climbing on Everest, and two years attempting Lhotse.

Icefall Bypass?

70-year-old French alpinist Marc Batard twice, in 2021 and 2022, attempted to establish a route to bypass the Khumbu Icefall by climbing on the flanks of Nuptse. Nuptse serves as the southern wall above the Icefall. The Benegas Brothers advocated for this for many years but could never make it a reality because of objective dangers and the climbing difficulty. He returned in 2022 to test his new route and to set an age record for a no-Os summit but accomplished neither.

Routes

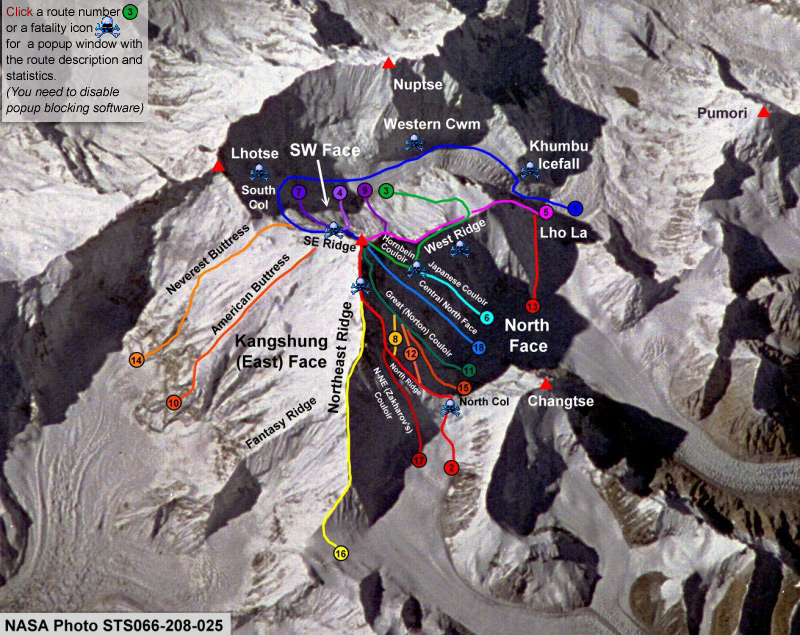

It is difficult to analyze the routes because they are often named after their geological feature, the national team, or even the person who first climbed them. But in, general, there are about 20 climbing routes identified on Mt. Everest.

There are three faces on Everest: the Southwest Face from Nepal, the East Face, aka Kangshung Face, from Tibet, and the North Face, also from Tibet. Of these, the Kangshung Face has seen the fewest attempts and even fewer summits.

Non-Standard routes

There are many, many variations on the non-standard routes. For example, climbing the standard Northeast Ridge to the summit and returning via the Great Couloir or the North Face. The Southwest Face is also popular; this variation includes the Bonington Route but also climbing via the Rib.

While the vast majority of climbers on the north side take the Northeast Ridge route, they are joining the ridge in the middle. The first ascent of the true Northeast ridge was in 1995 by a Japanese team. They start at roads and end at 5,150 meters. One section of that route is called the Pinnacles and is extremely technical and difficult. It took them three days and fixed 1,250 meters of rope to navigate through this section.

An interesting bit of trivia is that through January 2024, of the 11,996 summits, only 249 (185 members and 64 hired) took a “non-standard” route, not the Southeast Ridge or Northeast Ridge. There were 84 (54 members and 30 hired) deaths on these climbs–34% of the total deaths, which partly explains why the standard routes are most popular with commercial operators–lower risks. The countries with the most summits on the non-standard routes are Nepal (67), Japan (26), the USA (27), S. Korea (23), the USSR (23), Russia (16), and India (1).

Everest Faces

This is a list by Face with descriptions that include the common names plus some used by the Himalayan Database.

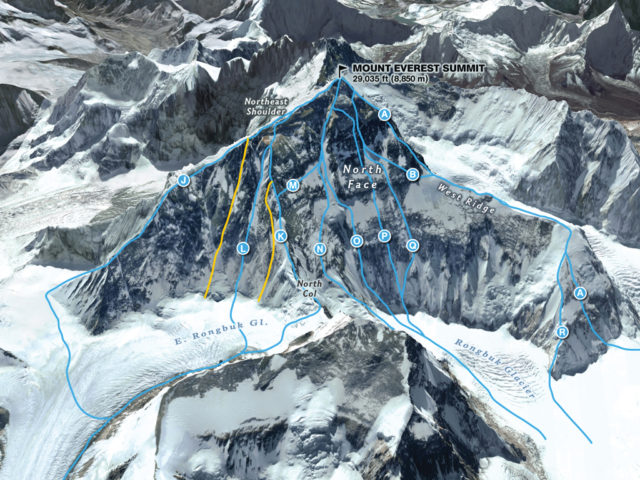

The illustrations are courtesy of National Geographic (Martin Gamache, Jaime Hritsik, Chiqui Esteban, Ng Staff Sources: 3D Reality Maps; The American Alpine Journal; The Himalayan Database; Ed Webster; East Face Imagery Courtesy Of Digital Globe @ 2012; Raphael Slawinski). National Geographic had a great piece about a proposed new route in 2015, which had an excellent article and animations but has since taken it down..

North Face

- (J) Integral N.E. Ridge – 1995 Japanese team

- (L) Russian Couloir – 2004 Russian

- (K) The Complete NE Ridge, N-NE

- (M) South Pillar, NE Ridge-N Face-Norton Couloir I – Messner Solo Route 1980 Messner Italian

- (N) American Direct – 1984 American

- (O) The Great Couloir aka Norton Couloir (White Limbo) – 1984 Australian

- (P) Russian Direct – 2004 Russian

- (Q) Japanese Supercouloir – 1980 Japanese

- (A) West Ridge Direct – 1979 Yugoslavian

- (R) Canadian Variation – 1986 Canadian

Using the Himalayan database, I researched the non-standard routes to get an idea of the volume on these routes. This is not an all-inclusive list.

| ROUTE | SUMMITS | DEATHS | LAST ATTEMPT |

| Khumbutse-W Ridge-N Face (Hornbein Couloir) | 2 | 1 | 1989 |

| Lho La-W Ridge | 19 | 2 | 1989 |

| N Face | 24 | 0 | 2004 |

| S Pillar | 45 | 1 | 2000 |

| SW Face, including the Bonington Route | 48 | 2 | 2009 |

| West Ridge- North Face- Hornbein Couloir | 8 | 0 | 1986 |

| E Face | 12 | 0 | 1999 |

Standard Routes

By now, you know two routes dominate Everest, with 11,742 out of the total 11,996 summits following the same basic route that was pioneered in 1953. John Hunt’s British expedition to the summit used the Southeast Ridge-South Col and Shi Zhang 1960’s summit via the Northeast Ridge-North Col.

Today, these routes seem to be caught up in guide politics as to which is safer, the degree of difficulty and the opportunity for success. An argument can be made for climbing from either side.

Southeast Ridge – South Col Route

| Pluses | Concerns |

| Beautiful trek to base camp in the Khumbu | Khumbu Icefall instability |

| Easy access to villages for pre-summit recovery | Crowds, especially on summit night |

| Helicopter rescue from as high as Camp 3 at 23,500’–if necessary | Cornice Traverse exposure |

| Slightly warmer sometimes, with fewer winds | Slightly longer summit night |

Northeast Ridge – North Col Route

| Pluses | Concerns |

| Fewer people (half of the Nepal side) | Colder temps and harsher winds |

| Can drive to base camp | Camps at higher elevations |

| Easier climbing to mid-level camps | More difficult with smooth or loose rocks |

| Slightly shorter summit night | Currently, there is no opportunity for helicopter rescue at any point |

Now, let’s take an in-depth look at both sides

South Col Route

Mt. Everest was first summited by Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and New Zealander Edmond Hillary with a British expedition in 1953. They used the South Col route. At that time, the route had only been attempted twice by Swiss teams in the spring and autumn of 1952. They reached 8500m well above the South Col. Of note, Norgay was with the Swiss, thus giving him the experience he used on the British expedition. The Swiss returned in 1956 to make the second summit of Everest.

This is a typical south-side climb schedule showing the average time and the distance from the previous camp, plus a brief description of each section. More details can be found on the South Col route page.

- Trekking Peak Acclimatization: Lobuche 20,161′

- Many teams now summit a trekking peak for acclimatization, thus reducing one trip through the Icefall.

- Basecamp: 17,500’/5334m

- Home away from home. Located on a moving glacier, tents can shift, and platforms melt. The area is harsh but beautiful, surrounded by Pumori and the Khumbu Icefall with warm mornings and afternoon snow squalls. With so many expedition tents, pathways and generators, it feels like a small village.

- C1: 19,500’/5943m – 4-6 hours, 1.62 miles

- Reaching C1, can be a dangerous part of a south climb since it crosses the Khumbu Icefall. The Icefall is 2,000′ of moving ice, sometimes as much as 3 feet a day along the edges. But it is the deep crevasses, towering ice seracs and avalanches off Everest’s West shoulder that create the most danger.

- C2: 21,000’/6400m – 2-3 hours, 1.74 miles

- The trek from C1 to C2 crosses the Western Cwm and can be laden with crevasse danger. But it is the extreme heat that takes a toll on climbers. Again, avalanche danger exists from Everest’s West Shoulder, which has dusted C1 in recent years.

- C3: 23,500’/7162m – 3-6 hours, 1.64 miles

- Climbing the Lhotse Face to C3 is often difficult since almost all climbers are feeling the effects of high altitude and are not yet using supplemental oxygen. The Lhotse Face is steep, and the ice is hard. The route is fixed with a rope. The angles can range from 20 to 45 degrees. It is a long climb to C3, but most teams require it for acclimatization prior to a summit bid.

- Yellow Band – 3 hours

- The route to the South Col begins at C3 and across the Yellow Band. It starts steep but settles into a sustained grade as the altitude increases. Climbers are usually in their down suits and are using supplemental oxygen for the first time. The Yellow Band’s limestone rock itself is not difficult to climb but can be challenging given the altitude. Bottlenecks can occur on the Yellow Band.

- Geneva Spur – 2 hours

- This section can be a surprise for some climbers. The top of the Spur leading onto the South Col has some of the steepest climbing thus far. It is easier with a good layer of snow than on loose rocks.

- South Col: 26,300’/8016m – 1 hour or less

- Welcome to the moon. This is a flat area covered with loose rock and surrounded by Everest to the north and Lhotse to the south. Generally, teams cluster tents together and anchor with nets or heavy rocks against the hurricane-force winds. This is the staging area for the summit bids and the high point for Sherpas to ferry oxygen and gear for the summit bid.

- Balcony: 27,500’/8400m- 4 – 5 hours

- Officially now on Everest, climbers are using supplemental oxygen to climb the steep and sustained route up the Triangular Face. The route is fixed with rope, and climbers create a long conga line of headlamps in the dark. The pace is maddeningly slow, complete with periods of full stop, while climbers ahead rest consider the decision to turn back or continue to the balcony. It can be rock or snow, depending on the year. Rockfall can be a deadly issue, and some climbers now use helmets. They swap oxygen bottles at the Balcony while taking a short break for some food and water.

- South Summit: 28500’/8690m – 3 to 5 hours

- The climb from the Balcony to the South Summit is steep and continuous. This is the most technical section of a climb from this side IMHO. While mostly on a beaten-down boot path, it can be challenging near the South Summit with exposed slabs of smooth rock in low snow years. The views of Lhotse and the sun rising to the east are indescribable at this point.

- Hillary Step – 1 hour or less

- One of the most exposed sections of a south-side climb is crossing the cornice traverse between the south summit and the Hillary Step. But the route is fixed and wide enough that climbers rarely have issues. The 2015 earthquake changed the Hillary Step. Climbers now report a large snow bulb area with no rock climbing as in the past. Previously, it was a short 40′ section of rock climbing, again fixed with rope, that created a bottleneck on crowded summit nights. Usually, there was an up-and-down climbing rope to keep people moving. The current ‘Hillary Slope” is still a source of bottlenecks.

- Summit: 29,035’/8850m – 1 hour or less

- The last section from the Hillary Step to the summit is a moderate snow slope. While tired, the climber’s adrenaline keeps them going.

- Return to South Col: 4 -7 hours

- Care must be taken to avoid a misplaced step down climbing the Hillary Step, the Cornice Traverse or the slabs below the south summit. Also, diligent monitoring of oxygen levels and supply is critical to make sure the oxygen lasts back to the South Col.

- Return to C2: 3 hours

- Usually, climbers are quite tired but happy to be returning to the higher natural oxygen levels regardless of their summit performance. It can be very hot since most climbers are still in their down suits.

- Return to base camp: 4 hours

- Packs are heavy since everything they hauled up over the preceding month must be taken back down. It is now almost June so the temperatures are warmer, making the snow mushy, thus increasing the difficulty. But each step brings them closer to base camp comforts and on to their home and families.

This animation is based on Alan Arnette’s personal experience of climbing on Everest 4 times and summiting on May 21, 2011.

Not all teams will use this exact schedule to summit from the Nepal side via the South Col. Some teams will only do one climb as they acclimatize on other peaks or at home.

For a more detailed description and animated route map, please see the South Col route page.

Northeast Ridge Route

Everest’s Northside is steeped in history, with multiple attempts throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The first attempt was by a British team in 1921. Mallory led a small team to be the first human to set foot on the flanks of the mountain by climbing up to the North Col (7003m). The second expedition, in 1922, reached 27,300′ before turning back and was the first team to use supplemental oxygen. It was also on this expedition that the first deaths were reported when an avalanche killed seven Sherpas.

The 1924 British expedition with George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine is most notable for the mystery of whether they summited or not. If they did summit, that would precede Tenzing and Hilary by 29 years. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, but there was no proof that he died going up or coming down. Irvine’s body has not been found, and there is speculation the Chinese found and removed the body and the infamous Kodak camera if it was with Irvine since it was not with Mallory.

A Chinese team made the first summit from Tibet on May 25, 1960. Nawang Gombu (Tibetan) and Chinese Chu Yin-Hau and Wang Fu-zhou, who is said to have climbed the Second Step in his sock feet, claimed the honor. In 1975, on a successful summit expedition, the Chinese installed the ladder on the Second Step.

Tibet was closed to foreigners from 1950 to 1980, preventing any further attempts until a Japanese team summited in 1980 via the Hornbein Couloir on the North Face.

The north side started to attract more climbers in the mid-1990s and today is almost as popular as the Southside when the Chinese allow permits. In 2008 and 2009, obtaining a permit was difficult, thus preventing many expeditions from attempting any route from Tibet. And it was closed to foreigners from 2020 through 2023 because of COVID and bureaucratic delays.

Now let’s look at the typical north side schedule showing the average time from the previous camp plus a brief description of each section. More details can be found on the Northeast Ridge route page.

- Basecamp: 17000′ – 5182m

- located on an extremely windy gravel area near the Rongbuk Monastery. This is the end of the road. All vehicle-assisted evacuations start here. As of 2024, there are no helicopter rescues or evacuations on the north side or for any mountain in Tibet.

- Interim camp: 20300’/6187m – 5 to 6 hours (first time)

- Used on the first trek to ABC during the acclimatization process, this is a spot with a few tents. Usually, this area is lightly snow-covered or just rocks.

- Advanced base camp: 21300’/6492m – 6 hours (first time)

- Many teams use ABC as their primary camp during the acclimatization period, but it is quite high. This area can still be void of snow but offers a stunning view directly at the North Col. It is a harsh environment and a long walk back to the relative comfort of basecamp or Tibetan villages.

- North Col or C1: 23,000’/7000m – 4 to 6 hours (first time)

- Leaving Camp 1, climbers reach the East Rongbuk Glacier and put on their crampons for the first time. After a short walk, they clip into the fixed line and perhaps cross a couple of ladders that are placed over deep glacier crevasses. The climb from ABC to the North Col steadily gains altitude with one steep section of 60 degrees that will feel vertical. Climbers may use their ascenders on the fixed rope. Rappelling or arm-wrap techniques are used to descend this steep section. Teams will spend several nights at the Col during the expedition.

- Camp 2: 24,750’/7500m – 5 hours

- Mostly a steep and snowy ridge climb that turns to rock. High winds are sometimes a problem, making this a cold climb. Some teams use C2 as their highest camp for acclimatization purposes.

- Camp 3: 27,390’/8300m – 4 to 6 hours

- Teams place their Camp 3 at several different spots on the ridge since it is steep, rocky and exposed. Now using supplemental oxygen, tents are perched on rock ledges and are often pummeled with strong winds. This is higher than the South Col in altitude and exposure to the weather. It is the launching spot for the summit bid.

- Yellow Band

- Leaving C3, climbers follow the fixed rope through a snow-filled gully, part of the Yellow Band. From here, climbers take a small ramp and reach the northeast ridge proper.

- First Step: 27890’/8500m

- The first of three rock features. The route tends to cross to the right of the high point, but some climbers may rate it as steep and challenging. This one requires good footwork and steady use of the fixed rope in the final gully to the ridge.

- Mushroom Rock -28047’/8549m – 2 hours from C3

- A rock feature that spotters and climbers can use to measure their progress on summit night. Oxygen is swapped at this point. The route can be full of loose rock here, adding to the difficulty with crampons. Climbers will use all their mountaineering skills.

- Second Step: 28140’/8577m – 1 hour or less

- This is the crux of the climb with the Chinese Ladder. Climbers must first ascend about 10′ of rock slab then climb the near vertical 30′ ladder. This section is very exposed with a 10,000′ vertical drop. It is more difficult to navigate on the descent since you cannot see your feet placement on the ladder rungs. This brief section is notorious for long delays, thus increasing the chance of frostbite or AMS.

- Third Step: 28500’/8690m – 1 to 2 hours

- The easiest of the three steps but requires concentration to be safe.

- Summit Pyramid – 2 to 4 hours

- A steep snow slope, often windy and brutally cold, climbers feel very exposed at this point. Towards the top of the Pyramid, climbers are extremely exposed again as they navigate around a large outcropping and experience three more small rock steps on a ramp before the final ridge climb to the summit.

- Summit: 29,035’/8850m – 1 hour

- The final 500′ horizontal distance along the ridge to the summit is quite exposed. Slope angles range from 30 to 60 degrees.

- Return to Camp 3: – 7 -8 hours

- The downclimb takes the identical route. Early summiteers may experience delays at the 2nd Step with climbers going up or summiteers having down climbing issues.

- Return to ABC: 3 hours

- Packs can be heavy since everything hauled up over the preceding month must be taken back down. It is now almost June, so the temperatures are warmer, making the snow mushy, thus increasing the difficulty. But each step brings them closer to base camp comforts and on to their home and families.

For a more detailed description and route pictures, please see the Northeast Ridge route page.

The Deadly Route?

As this chart shows, using the standard routes accounts for 73% of the deaths, with the Southeast Ridge dominating all deaths at 150 or 49%. This number is heavily driven by the 2014 ice serac release off the West Shoulder of Everest onto the Khumbu Icefall, taking 17 lives, and when 14 people were killed at Basecamp in 2015 after a 7.8 magnitude earthquake caused an avalanche off the Pumori-Lintgren ridgeline. Whether these were one-time events or ongoing concerns has yet to be determined. Therefore, climbers must make their own decisions as to the safer standard route.

Here is the summary update with 2023 statistics:

|

Reason |

Northeast Ridge |

Southeast Ridge |

Other Routes South |

Other Routes North |

total |

|

Avalanche |

7 |

40 |

15 |

16 |

78 |

|

Fall |

18 |

31 |

18 |

8 |

75 |

|

AMS |

12 |

29 |

0 |

5 |

46 |

|

Exposure/Frostbite |

10 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

26 |

|

Illness (non-AMS) |

5 |

18 |

2 |

1 |

26 |

|

Exhaustion |

12 |

15 |

0 |

1 |

28 |

|

Icefall Collapse |

0 |

16 |

3 |

0 |

19 |

|

Crevasse |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Disappearance |

4 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

18 |

|

other/unknown |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

|

Falling Rock/Ice |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Total |

71 |

175 |

45 |

39 |

336 |

|

% of Total |

21% |

52% |

13% |

12% |

Analyzing these death statistics more closely shows that on both sides, descending from the summit is significantly more deadly for members, with 46 deaths compared to ascending, with 12 on the Nepal side and 43 descending with six ascending on the Tibet side.

Everest Stats and Price

Summit Statistics through January 2024

Another popular post is my Everest by the Numbers – 2024 edition

The Himalayan Database reports that through January 2024, there have been 11,996 summits (5,899 members and 6,097 hired) on Everest by all routes by 6,664 different people. Those climbers who have summited multiple times include 1,571 members and 1,048 Sherpa, for 5,333 total summits. There have been 883 summits by women members.

Summits

The Nepal side is more popular, with 8,350 summits compared to 3,646 summits from the Tibet side. Only 1.9% or 224 climbers summited without supplemental oxygen. Only 35 climbers have traversed from one side to the other. Member summit success stands at 39%, with 5,899 who attempted to summit, making it out of 14,496 who tried. About 62% of all expeditions put at least one member on the summit. Few climbers from both Nepal and Tibet have summited, only 668. And even fewer, 155, have summited more than once in a single season. Almost only Sherpas, 78, have summited within seven days of their first summit that season. Kami Rita Sherpa (Thami) holds the record for most summits at 29 and Kenton Cool, UK, at 17 for a non-Sherpa. Seven Sherpa have 20 or more summits. Member climbers from the USA have the most country member summits at 906.

Deaths

As for Everest deaths, 327 people (199 Westerners and 110 Sherpas) died from 1922 to January 2024. These deaths are about 2.7% of those who summited for a death rate of 1.11 of those who attempted to make the summit. Westerners die at a higher rate, 1.38, compared to hired at 0.87. Descending from the summit bid is deadly, with 92 deaths, or 28% of the total deaths. Female climbers have a lower death rate at 0.81 compared to 1.14 for male climbers, and 14 women have died on Everest. The Nepal side has seen 217 deaths or 2.8%, a rate of 1.14. The Tibet side has experienced 110 deaths or 3%, a rate of 1.09. Climbers from the UK and Japan have the most all-time deaths at 17. Most bodies are still on the mountain, but China has removed many bodies from sight on their side. The top causes of death are avalanches (77), falls (75), altitude sickness (45), and exposure (26).

Latest: Spring 2023

In 2023, there were 667 summits, including only 12 from Tibet as it was closed but 671 from Nepal, and all but 3 used supplemental oxygen. There were a record 18 deaths of Everest climbers. 57% of all attempts by members were successful. Of the total, 61 females summited.

Everest compared to other 8000ers

Everest is becoming safer even though more people are now climbing. From 1923 to 1999, 170 people died on Everest with 1,170 summits or 14.5%. But the deaths drastically declined from 2000 to 2022, with 10,826 summits and 157 deaths or 1.4%. However, four years skewed the death rates, with 17 in 2014, 14 in 2015, 11 in 2019, and the record 18 in 2023. The reduction in deaths is primarily because of significantly higher Sherpa support ratios, improved supplemental oxygen at higher flow rates (up to 8 lpm) gear, weather forecasting, and more people climbing with commercial operations.

Of the 8000-meter peaks, Everest has the highest absolute number of deaths (member and hired) at 327 but ranks near the bottom with a death rate of 1.11. Annapurna is the most deadly 8000er, with one death for about every fifteen summits (73:476) or a 3.76 death rate. Cho Oyu is the safest, with 4,044 summits and 52 deaths or a death rate of 0.40, with Lhotse next at 0.38. Of note, 79 Everest member climbers, out of 200 members, died descending from the summit, or 39%. K2’s death rate has fallen dramatically from the historic 1:4 to around 1:8, primarily because of more commercial expeditions with huge Sherpa support ratios.

Cost

In my post on “How Much Does it Cost to Climb Mt. Everest-2024 edition,” I use the headline for 2024 that prices continue to increase from all operators on both sides. The increases are because of the rising Chinese permit fees, more Nepalese regulations around minimum pay and insurance, and a strong environment of supply and demand from clients. As I said before, there is an insatiable demand to climb the world’s highest mountain.

So, do you have to be rich to climb Everest in 2024? Well, maybe richer than a few years ago now that it costs about the same to attempt Everest from the Nepal or Tibet side. However, the Nepali operators have always been willing to deal, so take their list prices as an opening bid. With a strong tourism business, Nepali companies are still in the mood to make deals. So I wouldn’t be surprised if you could get on a low-end, essential services-only trip for $30,000. As for dealing with foreign operators, don’t bet on a significant discount. It’s customary to offer a little off if you pay a year in advance, but that’s about it. They fill their teams months in advance, so there’s little incentive to discount.

The price range for a climb with a Nepali-based, all-Sherpa-supported team is around $45,000 on either side. If you want to climb with a Western outfit and a ‘Western’ guide, i.e., non-Sherpa, it runs around $70,000, and a fully custom climb will break $115,000, going as high as $225,000. Over the past ten years, companies with Western guides on the Nepal side have increased their average prices from $64,000 to $71,500 today, while Nepali guides have gone from $35,000 to $45,000 but heavily discounted by up to 25%. On the Tibet side, prices have exploded from $32,750 to $75,000.

Summary

I am often asked which side or route is safer, and my answer is to pick your poison.

By now, you can see the non-standard routes are the domain of the elite and highly skilled alpinists, and even with their talent, the death rates soar. On the standard routes, the south has the Khumbu Icefall, and the north has the Steps and weather. However, these numbers clearly show the south has a larger death rate.

In spite of the Icefall dangers, I think most operators will say the south side is safer and slightly easier.

But the real answer is no one knows for certain what each season will bring. So train hard, get skills on low mountains and altitude experience on another 8000m mountain before Everest and go with a team you can count on in an emergency.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Preparing for Everest is More than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountain experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp 2016

2 thoughts on “Comparing the Routes of Everest – 2024 edition”

Chinese made it in 1960? Not even close. Important to say what really happened.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1960_Chinese_Mount_Everest_expedition

Comments are closed.